How to Get Them to Care

Hello Spontanes(?), Spontaneouses (?)—

Still working on a name to call you regular readers of this bi-weekly newsletter, Structured Spontaneity.

Looking forward to the end of January? Here in Vancouver, the crocuses are popping out of the soil, the magnolia trees are budding, and you can just smell spring on the horizon. If you peer really, really, really hard into your screen, you just might spot the still-low sunshine that’s pouring through my office windows hidden somewhere in these pixels.

No promises, though.

Today, I’m writing to share a literally awesome piece of digital art that was launched recently. No, I’m not talking about an NFT—thankfully, you can put your blockchain explainer guide to the side. I’m talking about something much weirder, more absurd, and, therefore, more beautiful.

I’m talking about the latest work from the best artist you’ve (probably) never heard about: Jonathan Harris.

As you read this email, I want to invite you to think about this question:

How does what we see on the Internet influence the most basic tools we use for “leadership” and “communication”?

Don’t worry: I’m here to ground the abstract in the practical and help you connect the dots.

Let’s start here. When I was in my twenties, I was deeply affected by a philosopher named Marshall McLuhan. You may not have heard of McLuhan, but you’ve almost certainly heard someone reference some of the phrases he invented—like “global village” and most famously, “the medium is the message.”

McLuhan was an English professor who was born near the beginning of the 20th century, which meant that he had a front-row seat for a massive transformation in how human beings communicate. In the late 1800s, of course, the major communications technology at the time was print. Books were expensive to produce and sell, so there were gatekeepers that ensured only the “best”—whatever that meant—made it to booksellers’ shelves. The most efficient way of disseminating information was in newspapers, and because of this, society prized an idea called “literacy,” which was the basic requirement of print. You couldn’t understand the world if you couldn’t read about it; to read (widely) was considered to have an understanding of the world.

Social systems, educational systems, political systems, etc. were all directed towards this crowning idea of literacy—so much so that literacy became an end in itself.

Try it out for yourself: go to your nearest cafe, watering hole, social media platform, and start arguing against literacy, and you’ll see how quickly you get laughed out of the room. (I know from experience.)

But then, in the 20th century, science and technology brought forward new “forms” of media—for example, radio, cinema, photography—and increasingly made these forms available to wider creators. Can we even imagine how jarring it would have been to have gone into a cinema for the first time and seen a distant part of the world with our own eyes? How would we be influenced by hearing the voices of our political leaders, rather than reading their ideas?

This was McLuhan’s jumping-off point. When he said, “the medium is the message,” he’s reframing something that most of us were taught in kindergarten—it’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.

Put slightly differently: how you say it changes the meaning of what you say. One classic example is Orson Welles’ 1938 radio broadcast of the 19th-century novel, The War of the Worlds. The audience panicked. The radio station’s switchboard was a sea of flashing lights, and the building was suddenly full of people and dark-blue uniforms.

What crime had been committed? Not taking a book and putting it on the radio. The crime was upending the audience’s ideas of reality itself.

This wasn’t a prank—it was an experience of mass hallucination, hallucination in the truest sense of “seeing or hearing something which is not there.”

No wonder they called in the cops.

McLuhan began writing about mediums and messages in the 1950s, pioneering the study of what we now call “pop culture.” Fast forward 70 years—how’s that for a McLuhanian term that would have made no sense to H.G. Wells?—and we are inundated with new “forms” of communication.

Think about it: every time we want to “say” something to someone, we have to quickly determine which form we want to use. Do I email, text, or call? Do I post on Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, WeChat…? Is this, like, a post post or is this a temporary message that should dissolve as soon as they read it?

It’s no less complicated at work: Teams, Slack, email? A six-page memo? A slide deck? Face-to-face, all-hands, stand-up, sit-down?

It’s remarkable that we’re able to make these decisions so quickly. Actually, it’s beyond remarkable—it points our attention to what we might think of as a new definition of “literacy.” All of us are “literate” in Internet culture, so literate that we can “work” with the Internet with a level of nuance and understanding that would have been mind-boggling to the radio audience that listened to The War of the Worlds.

Sure, some of us are digital natives, and some of us are my 96-year-old grandmother. But even my grandmother Facetimes and “likes" posts on Instagram. (Sometimes she likes strange posts, but that’s beside the point.)

If the medium is the message, then how you say it changes the meaning of what you say.

A still from Jonathan Harris’ newest project, In Fragments

With McLuhan in the background, let’s turn now to Jonathan Harris. Jonathan was born in 1979, which puts him on the cusp between Generation X and the millennials. It’s a good frame to begin to understand his work.

Jonathan’s “art” is the Internet. Maybe it’s better to say that Jonathan’s art is on the Internet, about the Internet. In some of his early works, launched in the 2000s, Jonathan combined programming and design to create strange and beautiful work that commented on the way that we were all learning how to use what we were still calling “the Web.”

One of his most famous works from this period is called We Feel Fine. We Feel Fine was based on an algorithm that searched millions of “weblogs” (how cute!) on websites like Blogger (remember?), looking specifically for the phrases “I feel…” or “I am feeling…” The algorithm would then clip the full sentence, up to the period—for example, “I am feeling hungry right now.”—and then save this “feeling” to an immense database of human experiences that steadily increased at the rate of 15,000-20,000 feelings per day. These “feelings” were then represented back to the viewer as a playful Flash-based interface—for example, you could click on a dot that would show you the clipped sentence, stripped of any context.

The interface would let you sort and search the data, asking questions like: do Europeans feel sad more often than Americans? Do women feel fat more often than men? What were people feeling on Valentine’s Day? What is the saddest city in the world?

See what I mean about art on the Internet, about the Internet?

We Feel Fine was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, where it is part of the Permanent Collection.

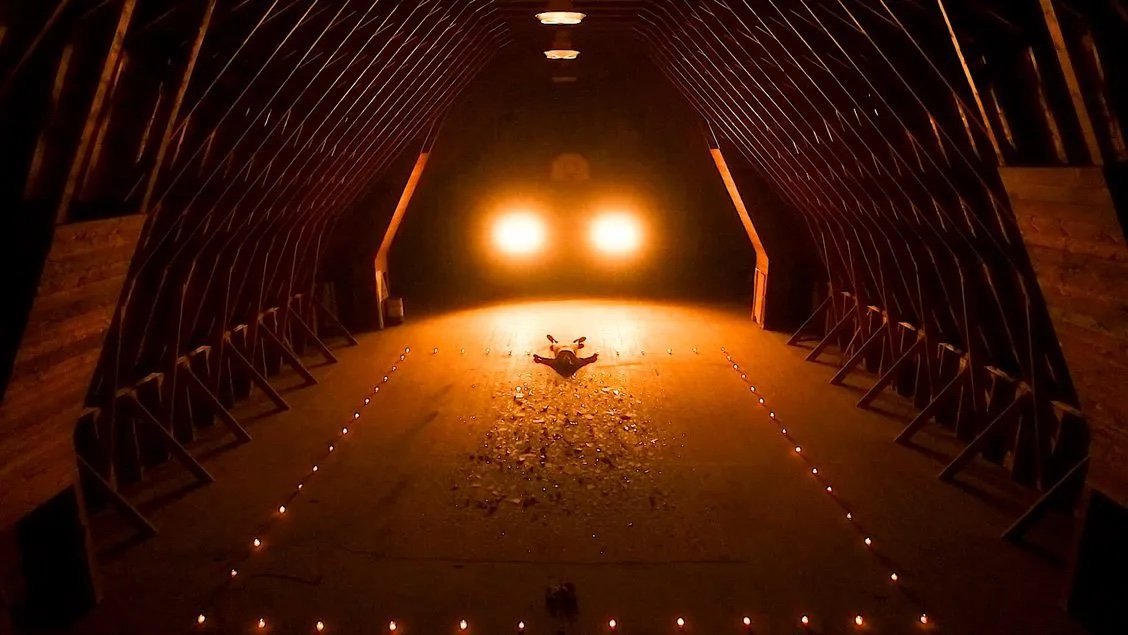

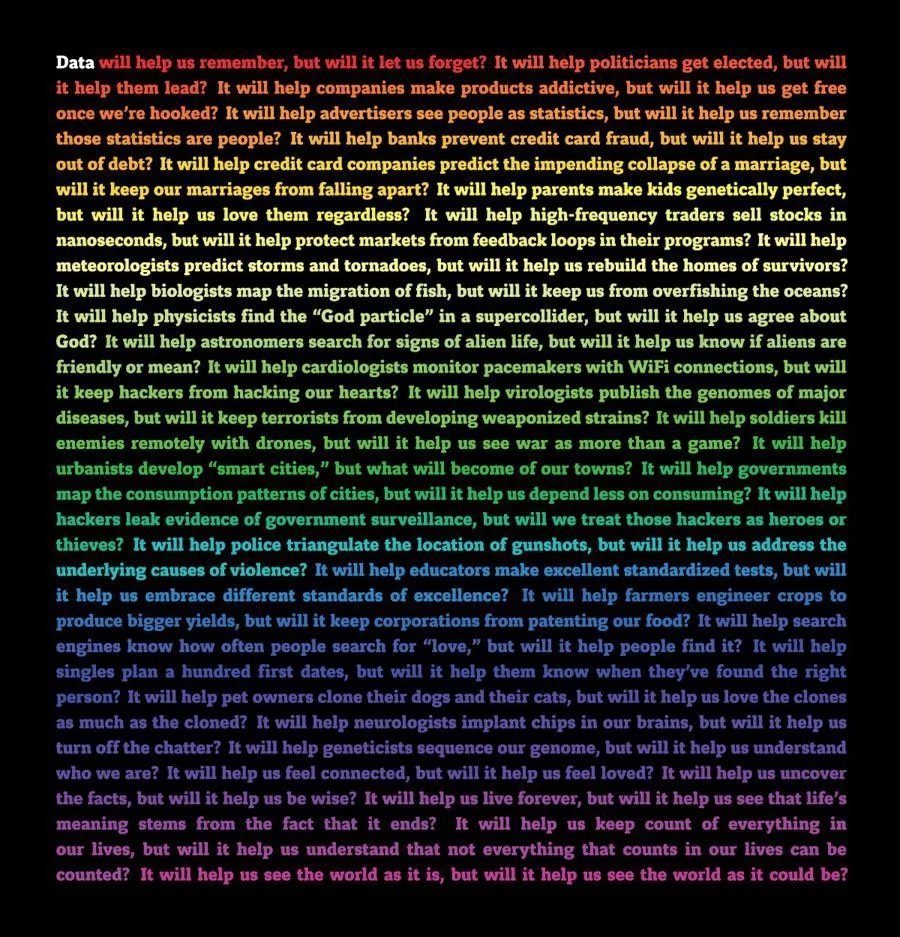

Jonathan Harris’ Data Will Help Us, 2013

Jonathan spent the 2010s making hopeful work about the Internet. But as we all experienced, around 2010 the Internet changed. Instagram was launched in 2010. Airbnb raised more than $100 million in 2011. In 2013, more than half of Americans owned a less-than-5 year old device called a smartphone.

Around then, we all started asking the same basic question:

How does what we see on the Internet influence the most basic tools we use for “leadership” and “communication”?

For 6 years, Jonathan went dark. Then, a few weeks ago, he launched In Fragments.

In Fragments is a major shift in direction. It’s no longer “art on the Internet, about the Internet”. It’s something weirder, stranger—more like “art on the Internet, about life off the Internet.”

Describing it doesn’t really do it justice or explain what it is. The basic story is that Jonathan inherited a family-owned farm in Vermont that had a strange and tortured history. Then, his mother died, and in an attempt to confront both his past and the farm, he performed 21 “rituals” that would “prepare our land (and myself) for the best possible future.

Jonathan filmed all 21 of these rituals, and together they represent the core of In Fragments.

Weird, right?

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw9xgtbqYU0?wmode=opaque]

Film 14: Hall of Mirrors

.

Clicking through the In Fragments website, I find myself thinking about McLuhan, and mediums and messages and forms. What Jonathan has created is explicitly a performance, in that all of these strange, deeply personal rituals are designed to be watched by us—the disembodied, global digital audience.

It’s performative, in the same way that Kim Kardashian is performative or that any influencer on Instagram is performative—or, in our context, the way that any brand or leader is obligated to perform whatever its strategists think it means to be leaderly and/or a good corporate citizen. But what Jonathan is performing is deeply intimate.

As a “user”, I don’t know what to do with it. I click. I watch. I look. Maybe I gawk a little; I definitely judge. But I also strangely become part of the In Fragments world. My curiosity is piqued. I want to know how his mother died, I want to know the sordid history of his farm, I want to know why he crafted these strange rituals the way he did, and I want to know whether it all worked.

In corporate tech/Internet terminology, I would say that I’m engaged.

In English, I would say that I care. Which is much, much more than I would say about most things I read on the Internet.

Don’t shoot me for saying this—but I don’t care about COVID. I don’t care about what most people, including me, post on LinkedIn. I don’t care about 99% of the email newsletters that hit my inbox, 99% of the posts I see on social media, or 99% of what I read on the news.

To be clear, I read all that stuff. I pay attention to it, I think about it; I’m not being grandiose and claiming something silly like FAKE NEWS! No. I think all of that stuff is really, really important. But it doesn’t make me care. It doesn’t even try to make me care.

It feels ironic that, as we all consume server farms worth of content that is trying so hard to get me to care, so little of it actually works.

There’s a big jump between outrage, anger, awareness, influence, sharing, posting, etc. etc. etc. and really caring about something.

That’s what I think about when I engage with In Fragments.

All stills from In Fragments

At the beginning of this email, I asked you to hold this question in your mind:

How does what we see on the Internet influence the most basic tools we use for “leadership” and “communication”?

Likely, most of you don’t consider yourselves “artists.” It’s more likely that you think of yourselves as “communicators,” “marketers,” “coaches,”“leaders…” and maybe among all of you there are even a few explicit “storytellers.”

But if you’re a “leadership communicator,” you’re probably asking questions like:

What qualities of leadership is my audience looking for?

What new forms are available to me now that weren’t yesterday?

What do I need my audience to “know” and what do I want my audience to feel as they experience it?

How do I get people to care?

Right now, there are a lot of people out there who are creating content that’s not worth caring about. No wonder there are a lot of people who don’t care.

This is a broken model. The human soul won’t make it last. You can only subsist on junk food for so long.

I think it’s telling that there are millions upon millions of “content strategists” out there, but comparatively fewer “medium strategists.” To think about how our audience experiences our message is to raise yourself to the level of art.

When we get to this level, we can set the how-to aside. We get to explore, experiment, we get to make the rules ourselves.

We get to care. And maybe that’s what will get other people to care too.

If you’ve got some time, click around In Fragments. Then, go to Jonathan’s website and check out some of his other work.

It’s weird. It’s strange. It’s absurd. It’s human.

Maybe that’s the message in the way the Internet works.